Is everybody listening?

Methane reduction continues, but are we playing to an emptying house?

By Frank Mitloehner

My job gives me the opportunity to travel around the world, and that never gets old for me. However, some journeys are exceptionally memorable and fruitful, managing to stand out among so many other worthwhile engagements that I’m privileged to be part of.

That was the case earlier this week when I was in Rome to participate in the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s Global Conference on Sustainable Livestock Transformation. It was a wonderful, spirited gathering of some of the best minds in the livestock and related sectors – including farmers, NGOs, academics, ambassadors, and ministers – all coming together to share ideas, viewpoints, research and fellowship. Kudos to the United Nations for continuing to provide the forum for this essential conversation. Never has it been more crucial to advance the dialogue – and find solutions – to food shortages and global warming.

There is value in seeing the issues we are aiming to tackle from various perspectives, in recognizing and respecting differences, in seeing another path perhaps not considered before. If nothing else, it reinforced in me that we need to work harder to communicate that lasting change in animal agriculture is possible – and that it is necessary.

I am convinced we can substantially reduce the sector’s methane emissions, as we must. Even if you are of the mind that doubling our aggregate food production by 2050 is an overstatement, suffice it to say business as usual is going to result in our falling way short of meeting the nutritional demands of nearly 10 billion people. Population is growing rapidly, even exploding in certain regions. We’re going to have to feed more people in the coming years, and that will obviously call for greater output from our farmers.

But there’s a conundrum: Already animal agriculture is emitting too much methane, so how do we increase production while decreasing emissions?

My work is focused on the latter, which, incidentally, can boost the former. Day in and day out, we are doing research and sharing information aimed at a healthier planet and a more sustainable food chain.

I’m not saying it’s easy to reduce methane in livestock. But we’re moving the needle, with more advances on the horizon. Just by managing manure differently, through anaerobic digesters, for example, we’re cutting emissions in California and winning again by piping the gas to industry partners who are using it as an alternative fuel source.

Meanwhile, there’s a gold rush to reduce enteric emissions, which make up most of the methane emissions from ruminant animals. (Read this simple explanation from NASA just for fun.) Companies new and old are endeavoring to develop tools that will take a bite out of cow burps, a must-do if we expect to achieve California’s mandate of 40% methane reduction by 2030. Feed additives have always been part of the conversation, and indeed, they are working. However, talks are evolving as products advance and become available to farmers. Vaccines and genetic selection are also being studied.

Each approach has pluses and minuses — and brings a lot of associated and understandable excitement. Feed additives aimed at making cows less gassy, to put it plainly, have been studied extensively and can integrate into intensive systems. On the other hand, selecting genetic traits for low-producing methane is arguably more complicated, and it will take time and research funding. Yet, it’s an avenue well worth pursuing for its potential to mitigate global warming and boost our knowledge in the field of genetic engineering. Vaccines are equally interesting, as they only need to be administered once. From then on, they can potentially limit animals’ methane production. And who knows … maybe these tools can be stacked. After all, no single solution is going to get us where we need to be.

In developing regions, where we expect herd sizes to increase significantly as population and demand for animal protein grow, improving animal health, feed quality and genetics will go a long way toward improving emissions relative to food production.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t state an obvious – albeit misguided – solution to our methane problem. That is, if we want to reduce methane, we should simply cut back our herds. As a matter of fact, that overly simplistic answer doesn’t begin to give us what we need to prepare for the future. That is, nutrient-dense food sources that make the most of our limited natural resources.

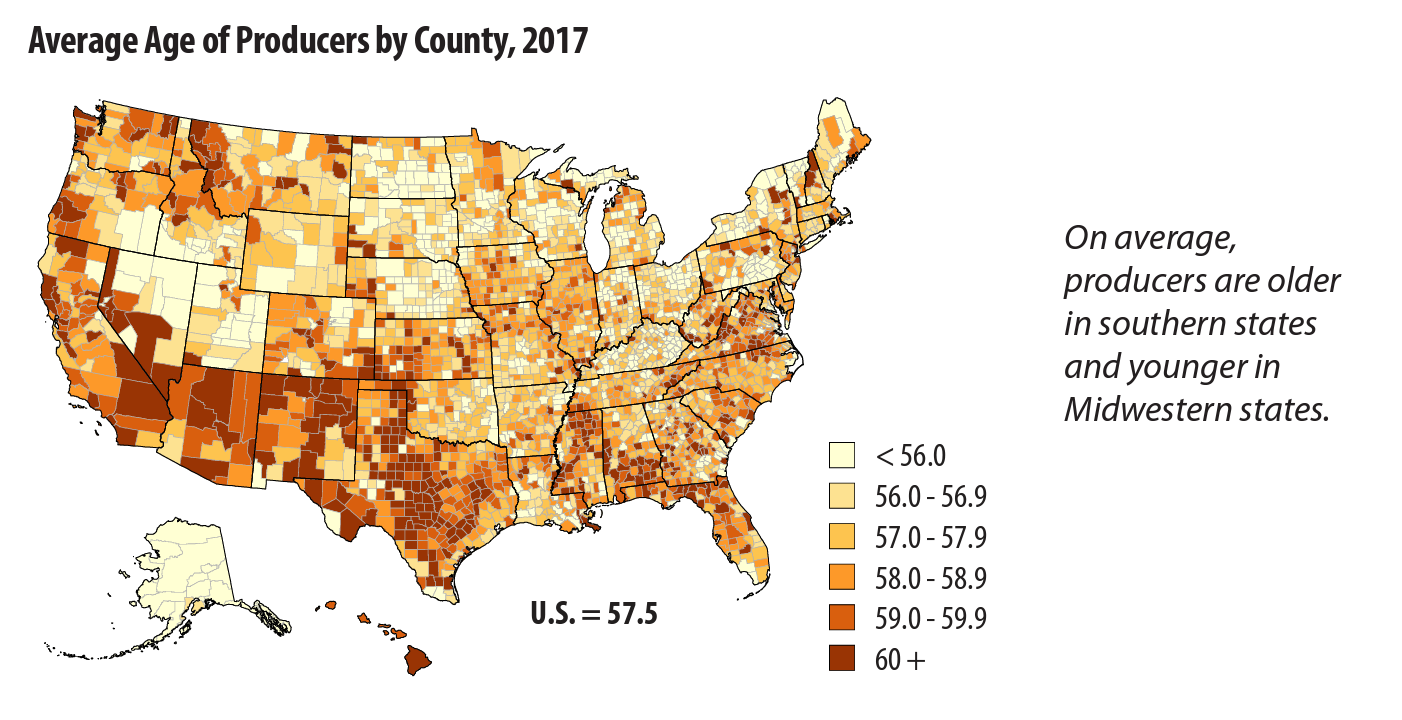

Make no mistake – we’re going to have to be more efficient, especially because our farmers are aging rapidly. According to the USDA and its 2022 census, the average age of a U.S. farmer, rancher or producer is 57.5 years, up from 56.3 years just five years earlier. The people who put food on our tables are getting older, and the pipeline is drying up. Subsequent generations are taking different career paths.

Can you blame them? Farming is hard work, and despite the fact that most of us can’t get through a day without reaching for the fruits of a farmer’s labor, we continue to malign them instead of supporting them in their efforts to be more efficient and sustainable. Shouldn’t we be thanking our producers each time we break bread?

Here's a thought: As our young people look for ways to be the change they want to see in the world, perhaps we can encourage them to add farming to their lists of possibilities.

It’s not a bad idea.

Especially if we’re there to help them along the way.