African Swine Fever and Lessons Learned in Prevention

What is African swine fever?

African swine fever (ASF) is a highly contagious disease with a mortality rate of up to 100% that infects domestic and wild swine. ASF has been found in more than 100 countries but has never entered the United States. ASF only infects swine; it is not a human or public health threat.

Transboundary animal diseases that can spread rapidly across the globe create food supply dysfunction and socioeconomic consequences and generate huge costs in prevention and eradication. Pork producers have a large role to play in preventing its spread.

The potential impact of ASF in the U.S.

There is no widespread vaccination or treatment for ASF. When ASF is identified, the only option to prevent further spread is depopulation, which devastates the global swine population.

“Not only is depopulating that number of animals shocking and heartbreaking, there are environmental issues when you have all these carcasses to compost as well as properly dispose of to stop the spread of the virus,” said Dr. Ragan Adams, a veterinary Extension specialist at Colorado State University Extension.

ASF in the U.S. would likely eliminate the pork export market, as most countries won’t import pork from countries with ASF outbreaks. Experts have run multiple scenarios of what economic impacts could be depending on how ASF spreads (i.e., through domestic swine, wild swine or insects), and some situations are as bleak as $50 billion in pork industry revenue losses over ten years.

“The loss of exports would have an immediate impact. Because we export more than 25% of our pork, production would have to shrink rapidly, and we’d have more pork than we consume,” Dr. James Roth, director of the Center for Food Security and Public Health at the Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine, said. “Prices would plummet, and there would be an immense loss in jobs as production scaled down to the new demand.”

Where did ASF originate?

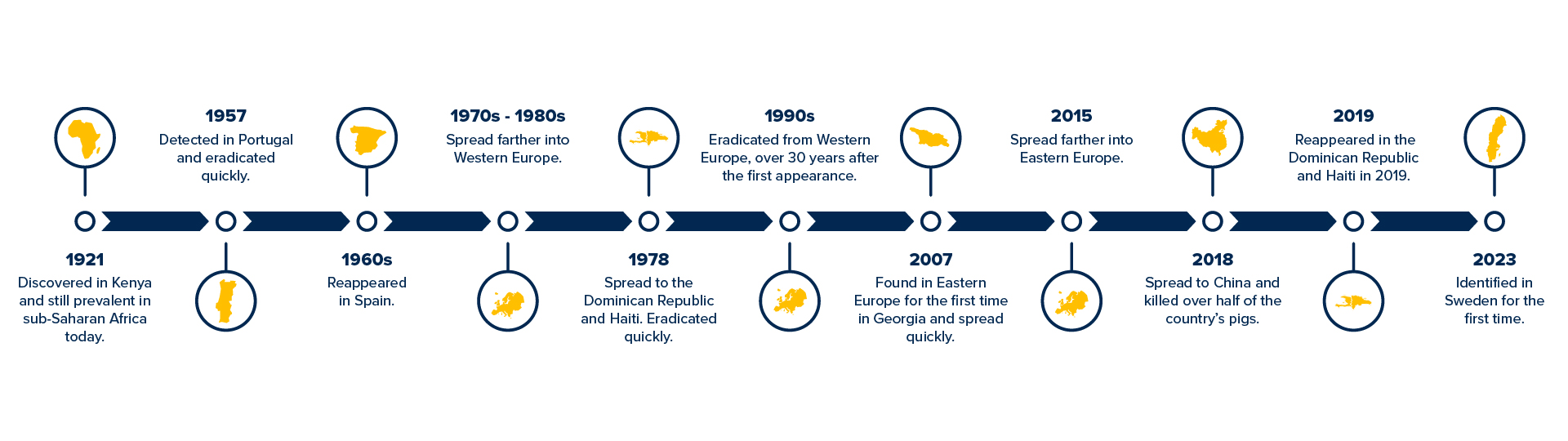

ASF was discovered in Kenya in 1921. The disease is still prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa today, where it is considered endemic. Wild boar, warthogs and soft ticks carry the infection in this area and make it difficult to eradicate.

“For decades, it was only in the southern part of Africa, so most of us weren’t overly concerned because we thought it would stay there,” said Dr. Roth.

In 1957, ASF spread from Africa for the first time and was detected in Portugal. A rapid depopulation of more than 10,000 pigs eradicated the virus until it reappeared in Spain in the 1960s. ASF spread farther into Western Europe in the 1970s and 1980s and was detected in the Netherlands, Italy, France and Belgium.

From its initial appearance in Western Europe, it took 30 years to control the spread. This is due, in part, to ASF entering the feral swine population, which makes it very difficult to control. Experts in the U.S. are concerned about a similar outbreak, as the U.S. is estimated to have six million feral swine.

ASF was found in Eastern Europe for the first time in 2007 in Georgia, where the disease spread quickly to neighboring countries and beyond. Eastern Europe is still battling the disease.

ASF spread to the Dominican Republic in 1978. In one year, the disease killed half of the country’s swine and spread to Haiti. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) worked with governments in both countries to eradicate ASF and prevent any spread in the U.S.

ASF reappeared in the Dominican Republic and Haiti in 2019. Experts are concerned about the proximity to the U.S. and U.S. territories (i.e., Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) and are working with governments in both countries to control the spread.

“When it was identified in 1978, the USDA assisted by depopulating all of the pigs on the island,” Dr. Roth “That became very unpopular, because that was a backyard source of food. So, this time, the USDA is providing advice, expertise, and assistance, but depopulation of all swine is not being considered.”

ASF was memorably in the spotlight in 2018 when it spread to China, the world’s largest producer of pork, and is estimated to have killed over half of the country’s pigs, which amounted to almost 25% of the global pig population. China’s pigmeat production dropped by an estimated 27%.

Most recently, in September 2023, ASF was detected in Sweden for the first time in a dead wild boar. It’s unclear how the disease reached the country, but it is assumed the spread was from human activity.

“We’ve learned a lot from what has happened in other countries,” said Dr. Roth, speaking about the Factors to Consider in a Potential Eradication Plan for African Swine Fever in the United States White Paper. “This is a very difficult virus. There are strains that are highly virulent that will kill 100% of infected pigs. But the virus can adapt and become less virulent, so it makes the pigs sick without killing them. This makes it harder to identify and harder to control. It remains to be seen what will happen in this hemisphere.”

How is ASF identified?

It is crucial anyone who works with pigs recognizes the signs of ASF. According to the USDA, these may include:

- High fever

- Decreased appetite and weakness

- Red, blotchy skin or skin lesions

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Coughing and difficulty breathing

- Abortions or sudden death (pigs commonly die within 10 days of infection)

As the USDA states, any suspicion of ASF should be immediately reported to state or federal animal health officials for appropriate testing and investigation. Pigs showing signs of ASF should be quarantined immediately.

How does ASF spread?

Swine can be infected with ASF by encountering the virus directly, indirectly or through insects.

Pigs may come into direct contact with the virus through infected domestic or wild swine that carry the virus. Once one pig is infected, it can easily infect an entire herd directly through contaminated feces, urine, saliva or respirations through coughing and sneezing.

While humans cannot contract or transmit ASF, they can indirectly spread the virus without knowing. Indirect transmission occurs by eating infected feed, including meat of infected pigs not properly cooked, or encountering the virus on clothing, shoes, equipment, vehicles or food waste.

Lastly, soft ticks, flies, leeches and swine lice act as vectors for the disease, feeding on infected pigs and indirectly spreading the virus to healthy pigs.

Emergency ASF outbreak plans

The Red Book Plan is the USDA’s emergency plan if ASF is detected in the U.S. Through this plan, transportation of infected swine, exposed swine and pork products would be halted immediately, and enhanced biosecurity practices would be put into place. Contact tracing would be conducted to detect other infected herds. Biosecurity would be enhanced to prevent further spread.

The National Pork Board’s AgView system is a pig-contact-tracing platform to be used in foreign animal disease outbreaks to make disease traceback and pig movement data available to the USDA and state animal health officials. AgView is an electronic way to record Premise Identification Numbers (PINs), which is a unique number permanently assigned to a location of livestock. PINs are used by animal health officials for animal disease traceability and emergency response.

Additional eradication strategies through the USDA would include quarantining infected areas, depopulating infected herds, establishing control areas and surveying control areas and free areas for signs of infection. While the USDA would consider possible vaccinations, there is currently no vaccine approved for emergency use in the U.S.

A key part of the emergency plan is conducting a public awareness campaign to educate the public on how they can help prevent the spread, minimize panic, address rumors and inaccuracies and maintain credibility for the government and industry to responsibly address the outbreak.

How have we prevented ASF from entering the U.S.?

Keeping ASF out of the country is the most important line of defense. At a national level, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and the Food and Drug Administration(FDA) are leading the charge in preventing ASF and preparing emergency plans.

“Prevention starts with what the USDA and U.S. Customs are doing to keep ASF from entering the United States,” Dr. Roth said. “The USDA has stepped up many activities to try to keep it out of the country, created awareness within the country of signs of infection and they are working with Haiti and the Dominican Republic to control it there.”

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection ensures no pork products (raw or cooked/dried meat, cured sausage, etc.) are brought in from countries with cases of ASF. Additionally, planes that travel from countries with ASF cases are thoroughly cleaned, and trash is properly disposed of to prevent ASF from spreading through contaminated items.

“If there is a global disease like African swine fever, you’d prefer to keep it out of the United States completely rather than have to battle it,” said Dr. Adams. “Once it’s in the country, it’s very hard to stop. We must keep it out of the country to secure a safe pork feed supply and maintain out ASF free trade position. Something as small as a sausage from a foreign country could result in an outbreak if it’s not cooked at the proper temperature to destroy the virus.”

The FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine is responsible for facilitating the development and approval of products to prevent the spread and infection of ASF. New animal drugs or food additives require approval by the FDA before being legally marketed.

Beyond these efforts, every commercial and non-commercial farm has a role to play in the fight against ASF. The USDA recommends biosecurity practices as a second line of defense to prevent ASF from infecting a producer’s herd. Dr. Roth stated that China’s commercial pork industry was able to recover relatively quickly because strict biosecurity was implemented immediately.

The best way to practice biosecurity is to limit farm traffic and ensure those on the farm are aware of protocols. Staff should routinely wash their hands or shower in and out of going onto the farm. ASF can be carried onto farms through clothing, shoes and equipment. Therefore, coveralls and equipment should be site-specific and not reused without cleaning. Additionally, all farm equipment and vehicles should be thoroughly washed and disinfected when coming into contact with a different herd.

It is essential to keep swine away from any wildlife, especially feral swine, and store feed in a safe space to prevent any cross-contamination. Similarly, pigs from different herds should not interact, and pigs that appear to be sick should be immediately isolated until testing can be done.

“I tell people, don’t panic about it, but plan for it,” said Dr. Adams. “Learn from the USDA, your Extension professionals, and your veterinarian the best ways to care for your animals to avoid disease. Having a good plan in place for your farm biosecurity is the best thing you can do for your animals.”

As ASF continues to spread around the globe, strong border control, strict biosecurity practices, watching for signs of infection and knowledge of the emergency plan are the most effective ways to protect our animals and ensure the sustainability of the U.S. swine industry.

For more information about ASF, please refer to the USDA APHIS website.

The CLEAR Center receives support from the Pork Checkoff, through the National Pork Board.