How Dairy Milk Has Improved its Environmental and Climate Impact

What is the difference between the glass of milk you enjoy today and the one that your grandparents drank decades ago? While they may look and taste similar, the present day one has a much lower carbon, water, and land footprint. In short, it’s better for the environment than ever before.

While there are many reasons for these improvements, reducing the amount of U.S. dairy cows, while increasing amount of milk a cow produces, has allowed the U.S. milk supply to grow on a year-by-year trajectory. These improvements that have stretched more than 70 years, have reduced land use by 90 percent, feed usage by 77 percent, and water use by 65 percent for each glass of milk produced. There are few, if any industries, that come close to dairy’s progress in shrinking its environmental footprint in such a short period of time.

There are several technologies that have aided improvements in productivity, including enhanced cattle genetics, nutrition research, and animal health.

How genetics in dairy cows have improved milk production

First and foremost, genetic progress over the past several years has significantly increased milk production from modern-day dairy cows. With artificial insemination, a farmer can breed their cows to the bull with the best genetics and make rapid genetic progress within one generation. Traditional breeding required multiple generations of cows to see the same type of genetic gains. Dairy farming in the U.S. has evolved to provide genetically improved cows with everything they need for high levels of milk production.

How animal health and welfare have improved milk production

The dairy industry has also improved veterinary medicine in regard to dairy cattle. It has made an effort to shift from treating sick animals, to preventing cows from becoming sick in the first place. Sick cows produce less milk for the remainder of their lactation. Cattle that produce less milk are subsequently less efficient and have a greater environmental footprint for every unit of milk they produce. Therefore, if dairy managers can prevent disease through vaccinating animals, promote management practices that reduce stress, and maximize cow comfort, the cows will be able to produce high levels of milk.

How understanding feed for dairy cows has improved milk production

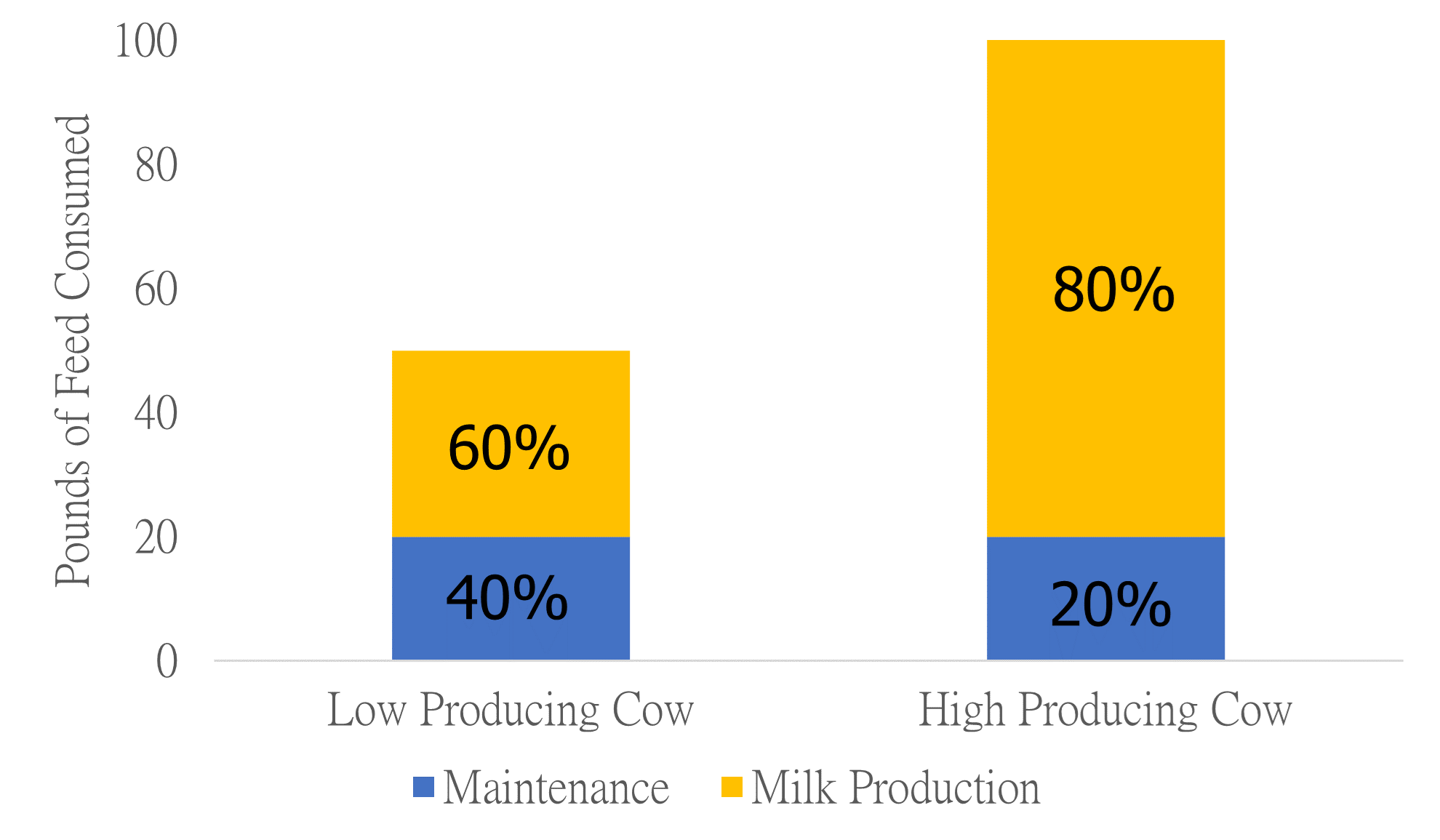

For cows to produce milk, they require a balanced nutrition in the form of carbohydrates, fats, protein, and minerals and vitamins. Research in cattle nutrition by the National Research Council (NRC) has created the Nutrient Requirements for Cattle. These are similar to the dietary guidelines that the U.S. Department of Agriculture provides for people, in that they provide recommendations for all cows from the day they’re born through the time they’re producing milk. The implementation of this research throughout the industry has helped ensure farmers are not over or underfeeding their animals to maximize both production and farm environmental impact.One main reason dairy cows have reduced their carbon footprint per unit of milk is due to the phenomenon known as the dilution of maintenance. Maintenance is the baseline nutrient requirements that a cow requires to survive. Regardless of whether a cow is producing milk or not, she will first put the feed she eats and the nutrients with it, towards staying alive. The additional nutrients she consumes then go toward milk production. Cows that produce more milk must consume more feed; however, higher producing cows use a greater percentage of the feed they consume for milk production. In essence, think of the maintenance requirement as the nutrients from the first twenty pounds of feed that a cow consumes. On top of this, a high producing cow requires eighty pounds of feed for her milk production capacity, whereas a lower producer needs thirty pounds of feed on top of the 20 pounds for maintenance. Although the lower producing cow consumes fifty pounds less of feed, she uses a larger percentage of the total feed consumed towards maintenance and not milk production (40 vs 20 percent; Figure 1). By decreasing the amount of nutrients that fulfill the basic needs of the cow, more nutrients are available for milk production (60 vs. 80 percent), which has greatly improved efficiencies.

Figure 1. Dilution of maintenance in high vs. low milk production cows.

How milk production from dairy cows has improved over the years

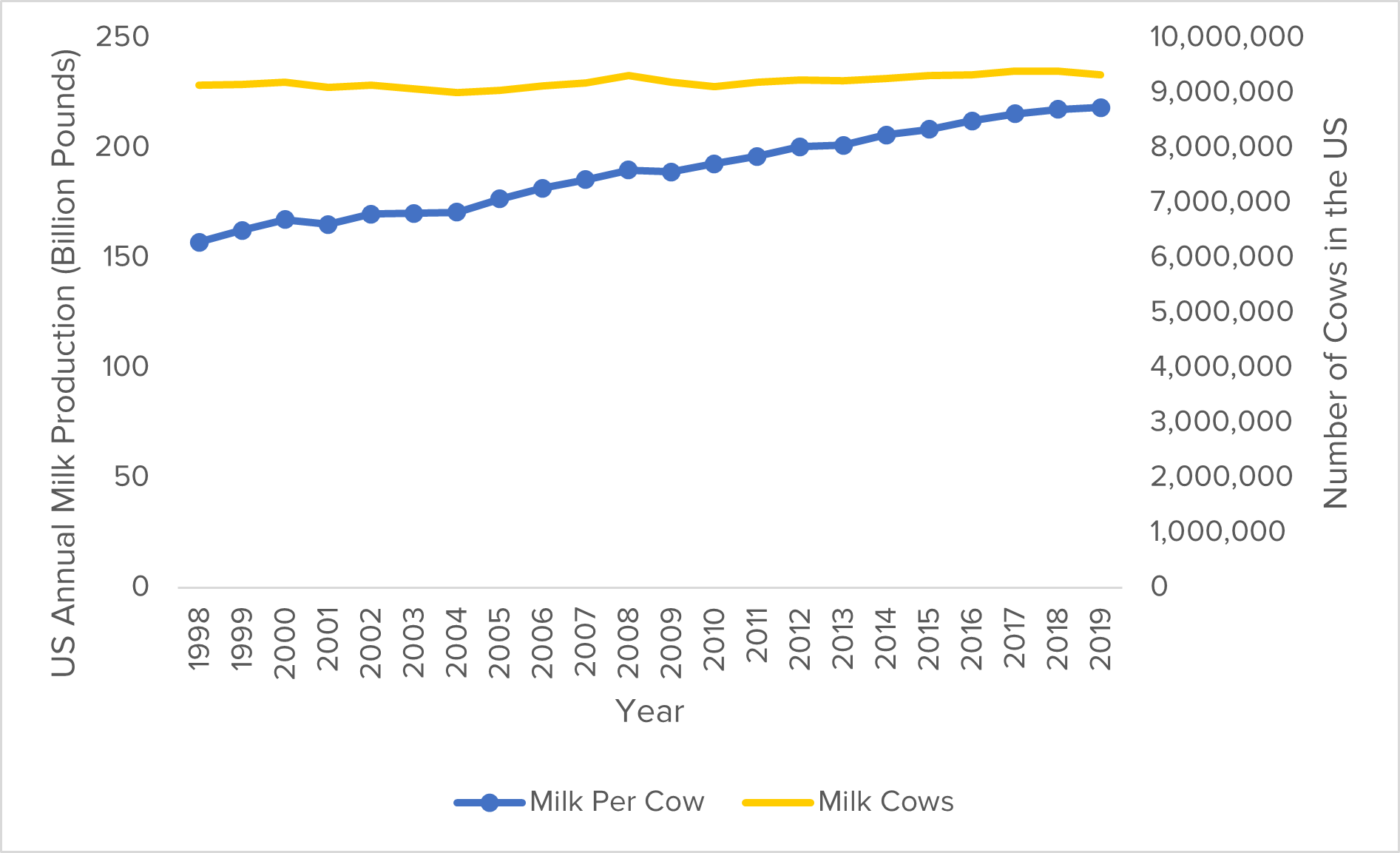

As noted, one of the U.S. dairy industry’s vast gains has been producing more milk with less resources. In 1944, the United States reached its peak dairy cattle population at 25.6 million animals. The herd size has since decreased, to the point where cow numbers hover just over 9 million annually (Figure 2). However, milk production in the U.S. continues to increase year upon and current production sits at 223 billion pounds of milk produced in 2020. This equates to just under 26 billion gallons and would be enough milk to fill 39,200 Olympic sized swimming pools. This milk then goes into making products such as cheese, yogurt, and fluid milk among others. The gains in milk production are not the result of increasing the number of cows but rather increasing the milk production productivity of the dairy industry.

Figure 2. U.S. annual milk production per year and number of dairy cows in the U.S. (1998-2019; Source: USDA ERS).

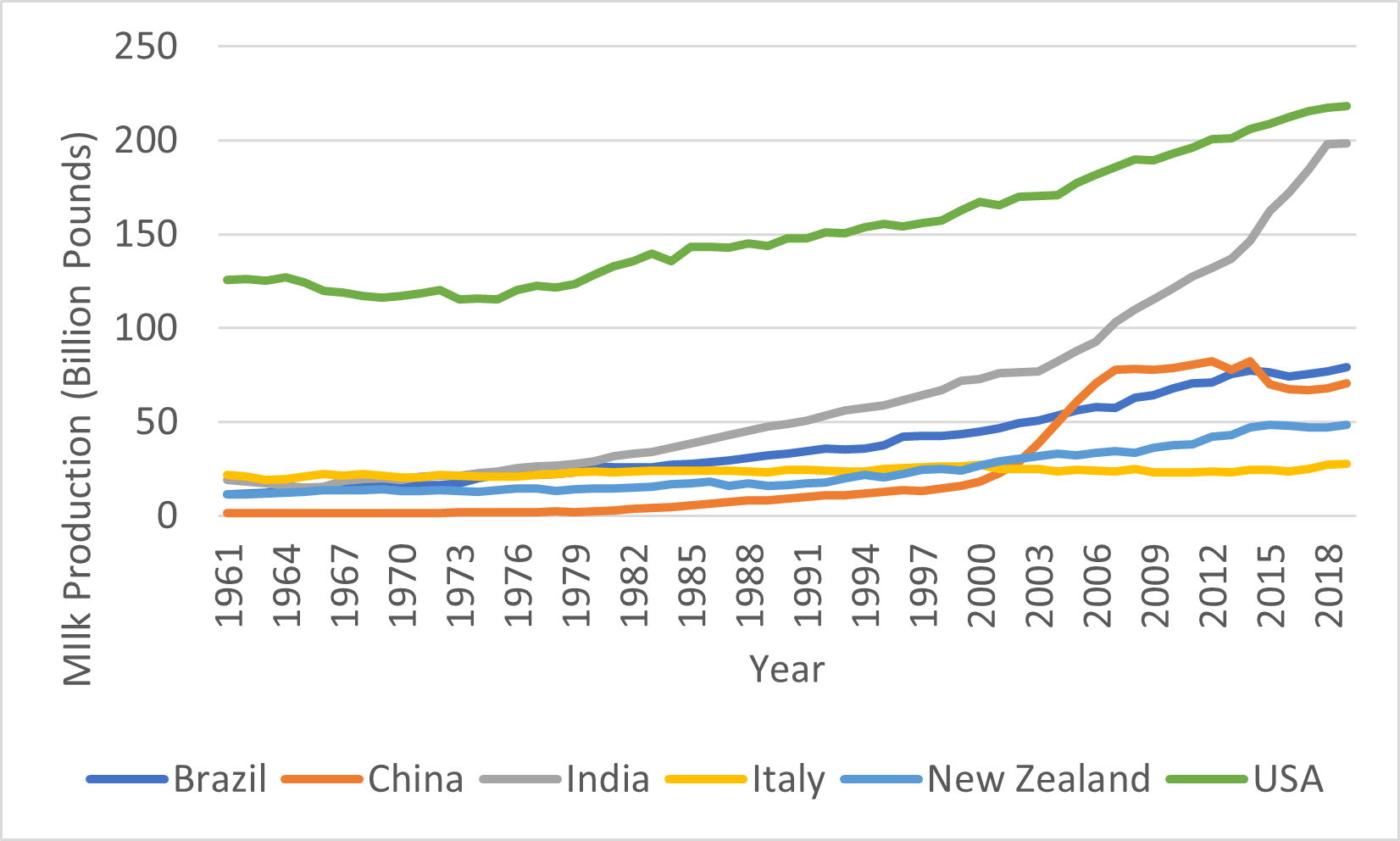

When comparing the milk production various countries, the United States immediately sorts itself to the top (Figure 3). Through significant weather events or economic challenges, the U.S. dairy industry has continued to improve productivity per cow year upon year in an almost exact linear fashion. While there is no one technology that has alone contributed to these productivity gains, they collectively build on top of each other to push the milk production potential of the 9 million cow U.S. dairy industry. Similarly, India has observed the same marked increases in milk production starting around the late 1990’s to have the second largest milk supply in the world. However, the majority of growth in the India dairy sector was in the form of adding more animals to today where they have over 300 million dairy cattle and buffalo .

Figure 3:Annual milk production across countries (1961-2019; Source: FAOSTAT)

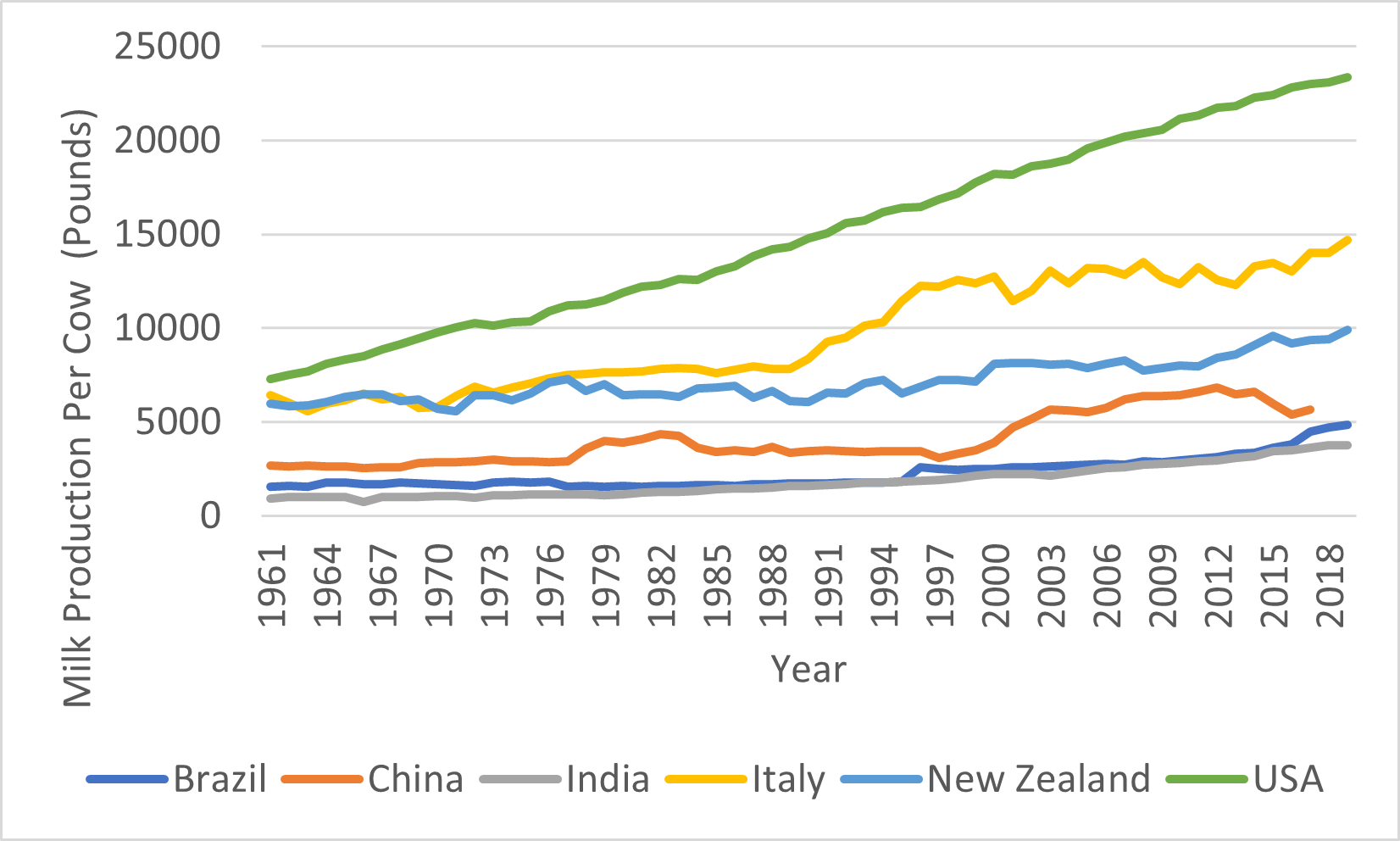

Figure 4: Annual milk production per cow across countries (1961-2019; Source: FAOSTAT). *2018 and 2019 years were removed for China due to estimated values for herd numbers

Global milk production and its impact on the environment

The country with the largest milk supply is India at over 420 billion pounds of milk produced annually from both dairy cows and water buffalo. Although marginal gains have been made for Indian dairy cows’ productivity, there has been a continued linear increase for U.S. dairy cattle annual productivity (Figure 4). Thereby the productivity of one Indian dairy cow is approximately 1/4 that of a U.S. cow.

Needing four rather than one cow to produce an equivalent amount of milk increases the amount of resources that are used for maintenance requirements and increases the environmental footprint per glass of milk produced. While there have been incremental gains made over the last few years, the South Asian country still has a way to go to reach the leading countries’ productivity levels. A similar story is true for other developing parts of the world, with Brazil observing low productivity per cow. However, the dairy industry in Brazil took off in the 1960’s through the importation of Gyr cattle from India. These cows were then crossed with the Holstein breed that is the most common dairy cow in the United States to create the Girlondo. This crossbreed can handle the sub-tropical climate of Brazil while also producing high levels of milk production. Further collaborations between these two countries have the possibility to vastly improve high producing cattle that are well suited for tropical climates.

Another country that stands out is China, where around the early 2000s they observed a dramatic increase in milk production (Table 3). Along with increases in total milk production, there has been an increase in milk productivity for China from ~3,000 lbs/cow in the early 1990s to today where it hovers around 8,000 lbs/cow (Figure 4). There has been an increased push in China to build larger scale farms to increase domestic food production to feed the largest population in the world. While major milk production efficiency changes have been made in China in recent years, there is still a large gap between U.S. and China productivity. Although, with time, China has the potential to become one of the largest and most efficient milk producers in the world.

Other historical dairy producing countries of Italy and New Zealand also experience high levels of milk productivity. However, the incremental gains they make on a year by year basis lag behind the observed changes in the U.S. dairy system. As milk continues to climb, the associated environmental footprint of production will continue to fall.

While much progress has been made in milk production efficiency across countries and production systems over the past couple generations, the industry may have not even scratched the surface of the efficiencies it can achieve. The world record cow, Selz-Pralle Aftershock 3918, produced 78,170 pounds of milk in 2018. While she comes from an above average herd that produces over 30,000 pounds of milk per animal, her daily average production totaled around 214 pounds per day. That is almost 350 percent greater than the current national average amount of milk produced per cow per year. If all cows in the U.S. were to reach that level of productivity, the U.S. dairy industry would only need 2.85 million cows to produce all the ice cream, milk, and cheese that we enjoy locally and export around the world.

The global demand for milk will continue to increase as populations become wealthier around the globe. We should not meet that demand by adding more cows but instead through increasing the productivity of the cows we currently have. As important as it is to increase milk production productivity, animal welfare must come first and foremost as decisions are made in growing global milk production. The supply necessary to feed a growing population is sure to be met via improved productivity while keeping cattle and the planet’s health in mind.

Conor McCabe is a Ph.D. student in Dr. Frank Mitloehner's lab at UC Davis.

How handling manure waste from dairy cattle impacts greenhouse gas emissions and climate change

Effective manure management practices on dairy farms can significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions from dairy cows, lowering their climate change impacts as well as keeping soil and waterways healthy.