Why U.S. Beef Isn’t Causing Deforestation and Land Use Change Elsewhere

Does eating beef in the U.S. lead to deforestation in places such as the Amazon? That’s an increasingly common question, to which the short answer is no.

But let’s dive into the long answer.

Deforestation is a type of land use change, sometimes referred to as land conversion. This is when land is permanently altered by humans, likely leading to a change in land cover, such as removing trees for agriculture use. This may have an impact on sources and sinks of greenhouse gases, but there are many factors that affect emissions on a piece of land.

Incorporating land use change in global cattle emissions is problematic, because not all countries clear land to raise cattle. In the U.S., nearly two-thirds of all agricultural lands are considered marginal land – meaning that land is unsuitable for growing crops or other uses, but is able to be foraged by ruminants. This mean we can take land, which isn’t suitable for much, and make it useful, turning the forage grown on it into protein people can eat.

The U.S. hasn’t deforested much land for cattle. In fact, ruminants have long been a fixture throughout the West. According to the National Park Service, 30-60 million bison roamed North America in the 1500s, as well as 35 million North American pronghorn, rivaling today’s cattle herd size.

But, if we eat less meat in the U.S., will that stop deforestation in the Amazon?

There is no doubt that destroying rainforest is highly problematic, but to blame it on Americans eating beef paints a distorted picture of global beef markets and emissions.

The argument is: Beef consumption anywhere leads to a global expansion of production and therefore puts pressure on the rainforest in order to establish pasture.

This is simply saying supply will meet demand, and if Americans stop reaching for beef as often as they do now, farmers and ranchers in the United States will turn to exporting more of their product, which will keep cattle producers in foreign countries from deforesting their homelands.

We talked about this in a blog.

In reality, Americans have already cut back on consumption, and companies have increased exports. Yet, we still see a country such as Brazil expand its grazing area.

In 1970, Americans consumed about 80 pounds of beef per person, compared to 57 pounds today. And in 1970, the U.S. exported less than 1 percent of its production but over 11 percent in 2018. We continue to see land use change in Brazil, even though U.S. beef consumption has dipped, because the two countries are producing different products, which are serving different markets.

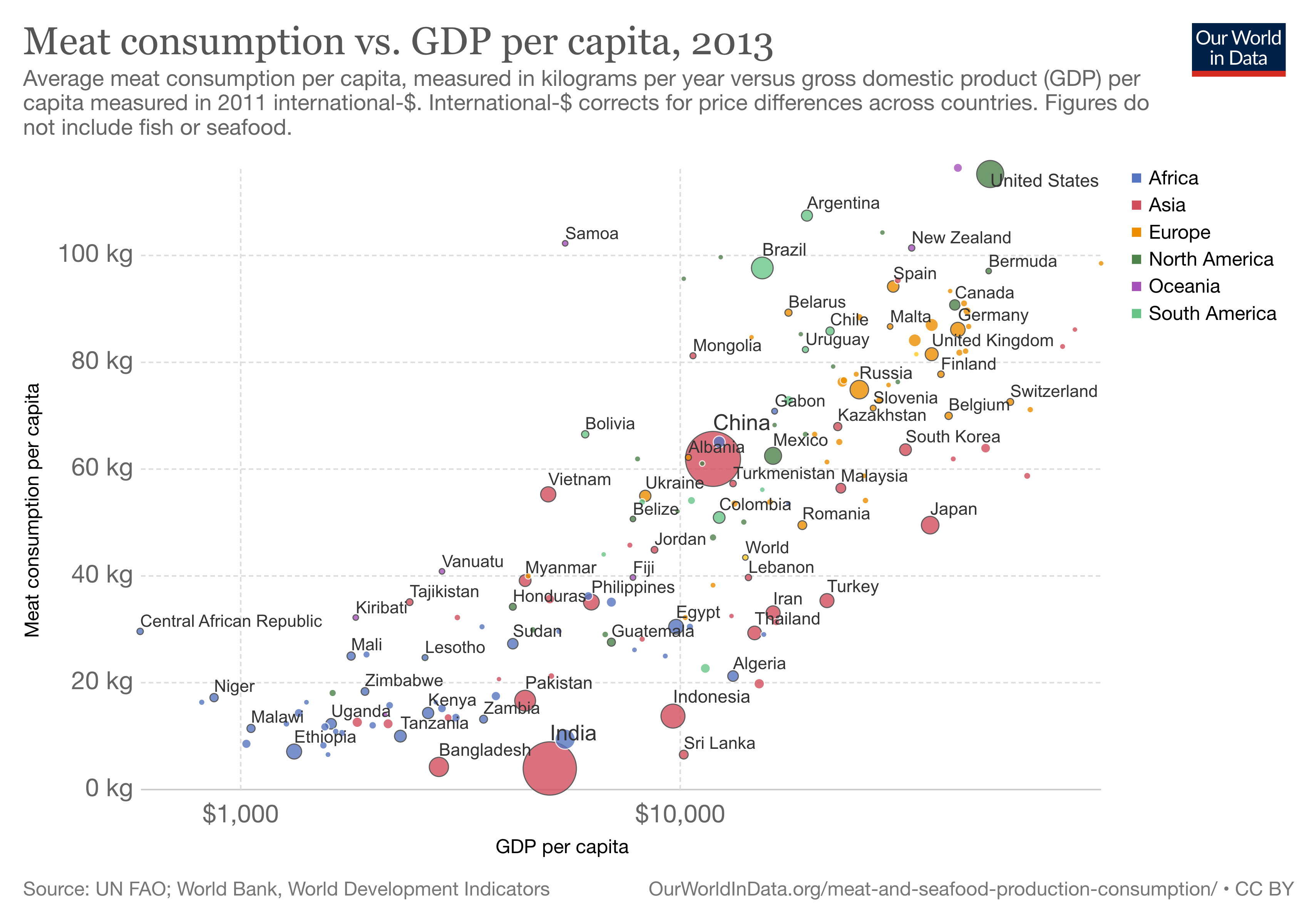

Beef from Brazil is not the same as beef from the U.S., which specializes in producing well-marbled, grain-finished beef. Conversely, Brazilian beef exports tend to be grass-finished, leaner and in general lower-quality products. As a result, these two countries are producing beef for very different consumers – the U.S. is targeting higher-income countries for exports, such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, where demand growth is slower, whereas Brazilian beef is headed to lower-income consumers in countries such as China, Chile, Egypt and Iran, where demand growth is much faster. In short, any potential reductions in U.S. consumption have been swamped by growing demand elsewhere.

Would an increase in U.S. beef exports eventually displace Brazilian beef exports in lower-income countries? Maybe, but it would take a considerable change in consumer choices and income in those countries. We have no evidence to indicate that would occur anytime soon, if at all. The predictions of the huge benefits of reducing U.S. beef consumption to reduce deforestation (i.e. land use change) are then, just based on unsupported assumptions.

Ultimately, a U.S. consumer eating less meat has not and will not displace consumption of Brazilian beef in Iran or China and therefore, decrease land expansion into the Amazon. That’s not how global beef markets work.

Can the U.S. help limit deforestation?

Eating or producing less beef in the United States won’t stop deforestation in other countries, especially as demand for beef rises. Yet, the U.S. may be able to help reduce emissions and land use change in developing markets by helping them to become more efficient.

The U.S. provides 18 percent of the world’s beef with 8 percent of the world’s cattle because of scientific advancements in beef cattle genetics, nutrition, husbandry practices, and biotechnologies. Sharing these innovations may help developing countries maximize production with less resources, and potentially reduce the need for land use change – such as deforestation – to keep up with global demand for beef.

Meaning that if we’re serious about limiting deforestation, it’s time we look to U.S. beef as a solution rather than a problem.

Use your head- the Amazon isn't our lungs

There have been reports that American beef consumption is to blame for the massive fires in the Amazon rainforest. What many of these get wrong is the patterns of production and consumption.